E&K Products – Builders of the ‘Jeep Approved’ Stratton Hydro-Implement Lift

An interview with Ernie Klimek III & Dave Klimek by Barry Thomas

(Note – An edited version of this interview was published in the 2021 summer edition of the Dispatcher magazine.)

Introduction

Ernie Klimek III has a lifelong history with Jeeps. He has owned several models, from his first CJ5 to his latest, a 2020 Jeep Gladiator. Thus, it was not unusual for him to be in a Jeep dealership one recent day, killing time while waiting for routine service to be completed on his wife’s Cherokee.

On a wall, Klimek noticed a series of photos of various Jeep models. The caption of one pointed out that Jeeps once were used as work horses on farms. That took Ernie’s thoughts back to his youth — to the era when he helped build the Stratton lift.

That evening, Ernie did some online research on farm Jeeps and found www.farmjeep.com. Seeing that our research into the Stratton Equipment Company had raised more questions than answers, he dropped us a note:

“Stratton would sub their work out to Sedlack Machine, a small fabricating shop on Cleveland’s west side. Sedlack Machine was bought out and re-named E&K Products. I know this because E&K is the family business. My grandfather and my dad started the business. Now my brother Dave, and Uncle Lee run the business today.

“I remember helping to build the implement lifts, painting them red, applying the “Jeep Approved” equipment decal, and then helping to crate and ship them. I was young, but if I remember correctly, E&K got the rights for the implement lift when Stratton left the business.”

I had spent five years researching the Stratton lift, mostly hitting dead ends. Now, here were answers to many of the Stratton questions.

Background

Stratton Equipment Co., of Cleveland, Ohio, produced the last of the “Jeep Approved” hydraulic lifts.[1] The label, “Jeep Approved,” was an important marketing tool, assuring the buyer that Jeep engineers had tested the equipment and certified it would perform as stated.

Monroe Auto Equipment Co. had produced its Jeep hydraulic lift from 1948 until around 1956. The Monroe lift sat in the bed of the Jeep. It could be removed, but its location reduced the Jeep’s versatility as a machine that could transform quickly from farm tractor to quarter-ton pickup.[2]

The Stratton lift’s “under the bed” design returned the Jeep to its “universal” vehicle status, while maintaining the improvement of the “plow geometry” made possible by the Monroe design.[3]

Information about the Stratton lift is scarce. Ironically, we have more information about the Newgren lift, produced in 1946, than we have about a lift made in 1966. Questions remain: When was the lift first produced? Who built the lifts? Who supplied the component parts? And most importantly, what happened to the lift when Stratton sold his business.

Ernie’s note made clear that answers are out there.

The interview

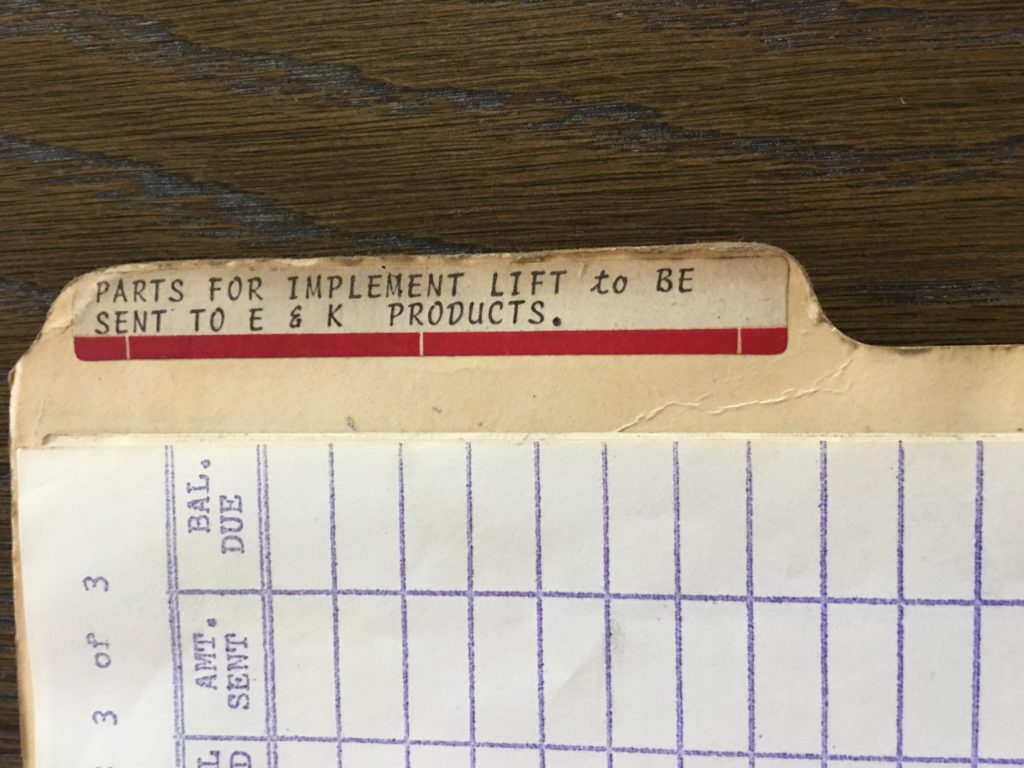

Ernie and his brother Dave, who now runs E&K, agreed to try to help us answer some questions about the Stratton lift. Dave has found several documents containing valuable information. We thought an interview format might be the best way to tell the Stratton and E&K story.

BT – I think we should begin by asking you, Ernie, what a young kid was doing on a shop floor?

EKIII – When it was Sedlack Machine, families weren’t allowed on the property. I remember walking down to Dad’s work with my mum and giving him a lunch through the gate at those times when he was working a Saturday. After it was E&K, it was all hands-on deck to help. I started pushing a broom and then doing other small, safe jobs. Those were long 14-16 hour days for Dad, as anyone would know who owns a family business. Saturdays included. Mum felt it was our way to be able to spend time with our dad. It was there that I started to learn to read blueprints, and I remember the implement prints as some of those first prints. Then my grandfather and Dad would show me the finished piece.

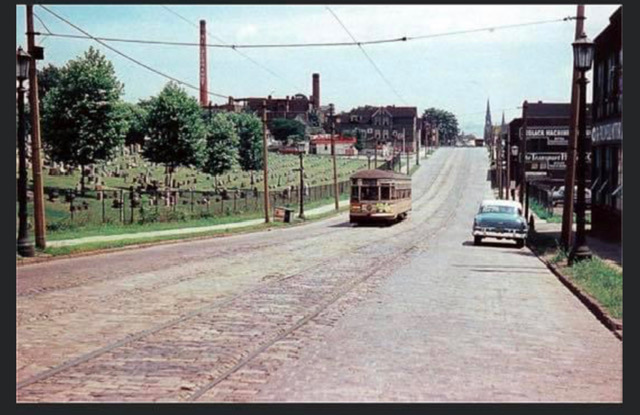

BT – Ernie, you sent me a picture of the Sedlack building from maybe the 1950s. Can you share a little more information about the neighborhood where you grew up and the business was located?

EKIII -The picture is looking east down Clark Avenue on Cleveland’s near westside. In the picture Transport Products was the back shop at 3815 Clark Avenue with Sedlack (later E&K) up front at 3809 Clark. We had the two-story and Transport Products was attached in the back. I played quite a bit in that shop yard. I got my bike up to 30 MPH (according to my speedometer) pedaling down that hill after it was paved.

We lived on 44th, grandparents on 46th, and great grandmother on 47th street off of Storer Ave. The Church was Christ Lutheran at 43rd and Robert. I went to school there. Everything in a small neighborhood. Everyone knowing each other.

Mr. Berghaus owned Transport Products. Transport did more utility bodies and mounted bucket lifts. We did more machining and accessories lifts. Phillips elevator was one of them. As E&K we continued with the lifts (Phillips old and new), Sideloader, implement lift and rendering truck bodies. Followed with pallet jacks and other lifting parts. We made fifth wheel plates for HEIL and shipped them to Milwaukee where they installed then on their tank trailers. We did machining and fabrication for a lot of businesses. Ruger, Stratton and Hunter, Kindt-Collins.

BT – Dave, I know you are the younger brother. Do you remember the Stratton lift? And when did you take over the family business?

DK – I remember the other Stratton products we were making better than I remember the lift. Like my brother said, we worked as a family. Some days good, some days not so much. I followed Ernie on the hacksaw when he moved to other equipment. After Ernie left for the Air Force, it was my brother Doug and me and Dad working with the rest of the family. (Yes, there were three of us boys). Doug did a lot of the painting. Doug left for the Air Force two years later and it was just Dad and me with the family. Dad’s health got worse, and I did more. He died in 1995, and I stepped up into his spot.

BT – Dave, you are to be congratulated on keeping the family business going for more than 50 years. That is an incredible feat. Not only that, but you have kept records that allow us to look back at the Stratton history. I was shocked when Ernie said that there might be documents, including prints, related to the Stratton. It has been my experience in researching Jeep accessories that the small companies have disappeared, and if they do exist, they have no records. Was good record keeping a part of how E&K did business?

DK – Thank you. At times it hasn’t been easy. Keeping good records was essential. When you are a small business, every decision you make can make or break you. The old records are key to what we do today. My Uncle and I take a lot of pride in continuing on the family business. In some ways we modernized, yet we still maintain the old-fashioned values. That’s what keeps our customers coming back.

BT – How did your family become the builders of the Stratton lift?

EKIII – My grandfather had been working for Sedlack Machine since he was 18. My great-grandmother knew the Sedlacek (original spelling) family and looked to get my grandfather a job. They ran a small machine shop down the street from my grandfather’s home on West 47th Street in Cleveland. This was in the 1930s. My grandfather started as a watchman, and eventually became a machinist. Over the years, Sedlacek Machine Shop wanted to be seen as more American, so the name was changed to Sedlack Machine, and they moved to a larger building on Clark Avenue.

My grandfather became more involved with the business side, as well as operating brakes, punch presses and lathes. Except for a 4-year hitch in the Air Force, my dad also worked for Sedlack Machine. When Mr. Sedlack started to let the business go, my grandfather and dad stepped up to reassure customers not to take their business elsewhere. One of those customers was Stratton. In 1967, Mr. Sedlack sold the business, contracts and machinery to our family: to Ernest & the Klimeks. E&K Products came to be at 3809 Clark Ave, in Cleveland. Once the family took over, we were all involved. Parents, grandparents, grandchildren, aunts, and uncles.

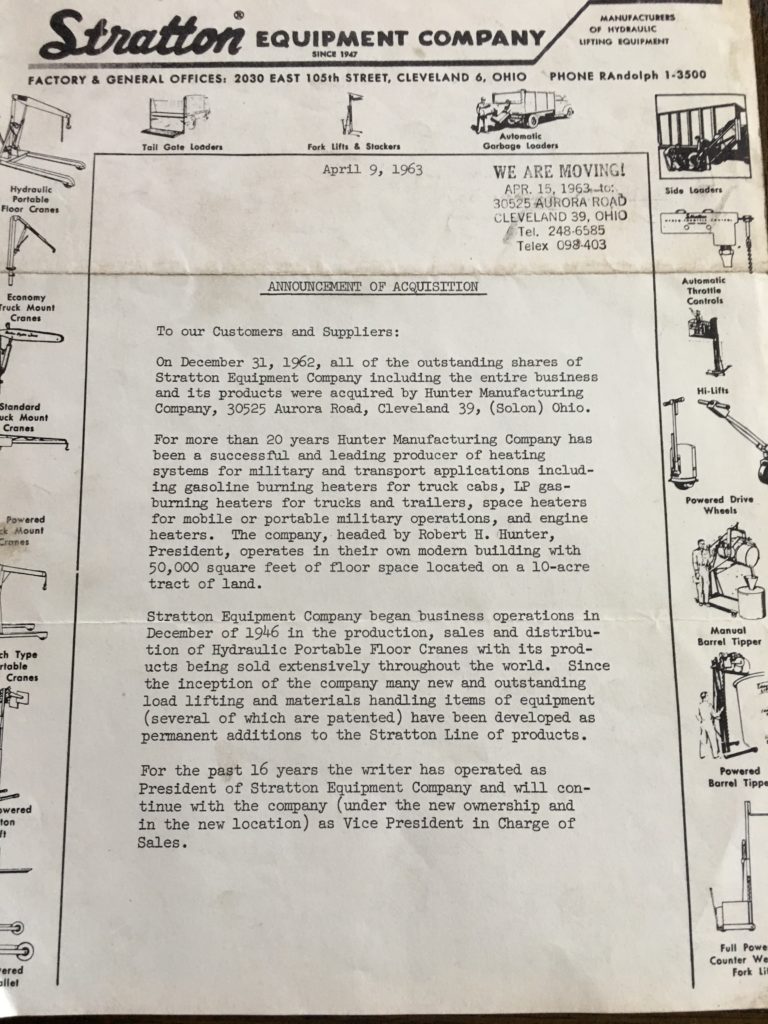

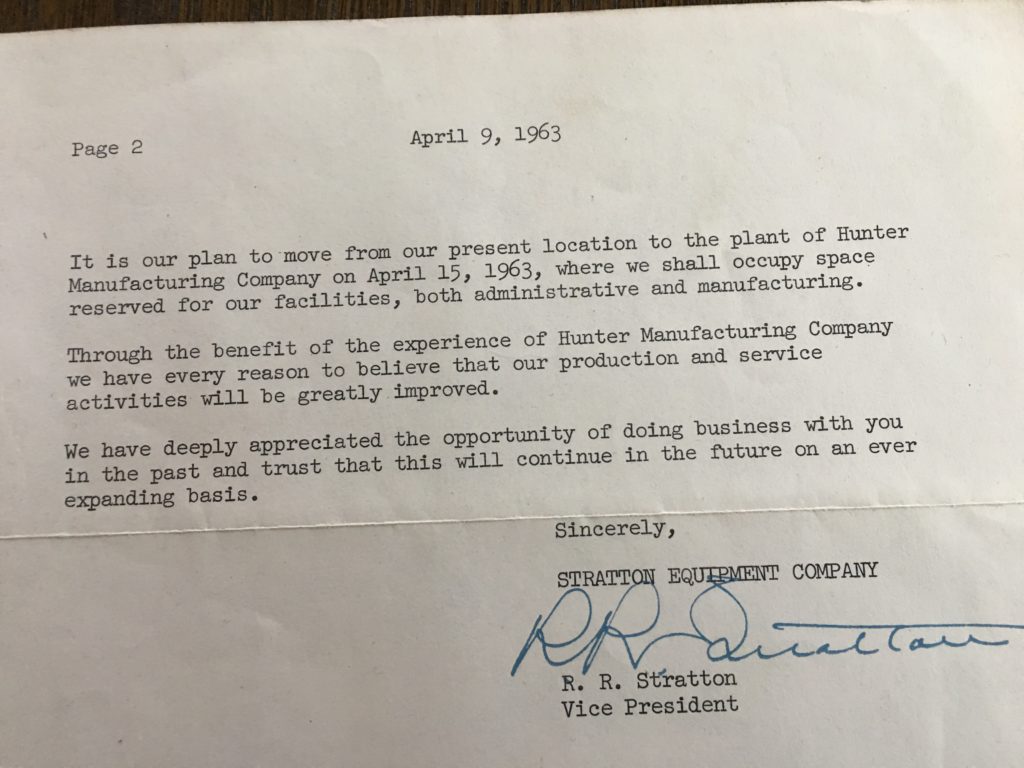

BT – Our research on Stratton dead-ended with the sale of Stratton to Hunter Manufacturing Co. You have provided us a 1963 letter from R.R. Stratton announcing the sale to Hunter. More importantly, you have provided a lift brochure that shows Stratton as a division of Hunter. Do you have any information on Hunter and what they did with the Stratton division?

EKIII – I don’t have a firm understanding, but my take at the time was they were completely incorporated into Hunter. When Hunter closed the Stratton division, some Stratton products were sold off (different floor lifts to RUGER Industries) and other Stratton products were no longer manufactured. I would guess about 1972 – 1974 on the closure. I was older when Dad shared the news and some of the drawings with me and said we got the rights for the lift. What that all entailed I’m not sure, but E&K Products would be your go-to source for the implement lift.

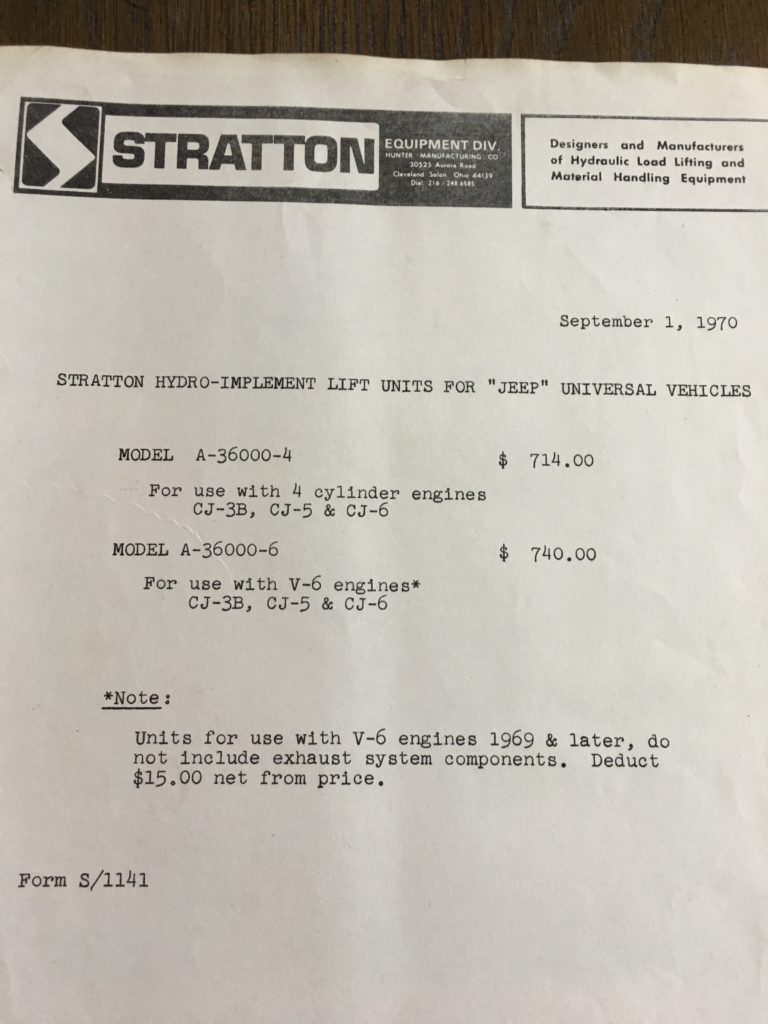

BT – An extremely exciting find was the price list from 1970. It is the first clue, along with your new information, we have seen regarding the lifespan of the lift. We had always thought that the sale of the lift might have ended with the sale to Hunter. Even if sales ended in 1970, Stratton sales would have lasted longer than Monroe, over a decade. The Monroe lift entered production in 1948 and Monroe ceased production around 1956. The Stratton price list from 1970 means that even if we accept the patent date (1960) as a starting point (and I believe production may have started a year or two earlier), the lift was available for a decade. With the E&K information, we can stretch sales (even if minor) into the mid-1970s. Prior to seeing the price list and hearing your story, we had assumed production of the Stratton lift stopped sometime in the mid-1960s.

There is one more thing to ask before leaving the price list. Do you have any information on how prices were set?

DK – Our costs were determined by material costs, labor hours, equipment hours, which included electrical, mechanical, and maintenance to operate that piece of equipment, overhead for office time and billing. That overhead was around 10 to 15 percent. I know this breakout because my grandfather shared it with me one day. It was the same on all items produced.

The material used was purchased from small flat stock steel and round stock suppliers. Spartan Steel was one of them. These were always low-end no. 1 or high-end no. 2 products. Think of lumber grades and apply to steel. They would be small volumes that were left after larger suppliers took their cut. The small suppliers would pick them up and market them to small shops like us. My grandfather would need so much, and the supplier would look for it from Republic, U.S. Steel, or other Cleveland area steel mills. We had a stock of certain sizes of flat, round or bar stock we used, and extra if the price was right. After shearing, if there was extra, it was set aside like you would do with wood pieces, perhaps to be used on a different job in the future.

There never was a large inventory of items available. Only if it was beneficial to have extras, then extras were made. If a length of round stock could produce 10 items, and only 8 were needed, 10 were produced to have extra. It never was producing 100 and have them lying around. All costs were controlled through the material, equipment, and labor pricing. If material cost went down, then extra may be made, as the end cost would be the same. We grandkids didn’t cost that much, so we reduced costs and could save on expenses while learning and having fun. What other kids could do this? We didn’t realize it was work!

Other items that were purchased, such as castings and hardware, were bought at the best cost break level. A box of bolts, vs. one or two. A roll of chain, vs. a couple of feet.

BT – You say there was never a large inventory of finished items. Do you know if Stratton would order a set number of lifts per month or were orders filled as they were received?

EKIII – I’m not sure if Stratton had a standing order from Sedlack or with us for X number of lifts a month. It wasn’t done that way. It was more, “We need two or three more. How soon can we get them?” I’m sure at some level there might have been more than that, but we lived at a time when your word was all it took. Reputations were at stake and no one wanted to ruin that. Especially a new business.

So I felt they were more on-demand for us. It might have been different initially for Sedlack.

BT – The number of Stratton lifts produced has always been a mystery. They rarely come up for sale, and the numbers we have tracked seemed more in line with the Newgren lift, with perhaps a few hundred sold. The Newgren lift was only in production for two years. The fact that E&K (and Sedlack before) was building the lifts “on demand” would explain the low production numbers and the fact that a stockpile of lifts has never been found.

Demand for lifts had fallen dramatically during the 1950s, and that may have been the reason Monroe left the marketplace. Willys and subsequent owners had greatly curtailed, or ceased, advertising the Farm Jeep by 1960. Public sales of the CJ3b ended in 1964. Around 1970, the CJ5’s fuel tank was moved from under the driver’s seat to under the bed, eliminating the possibility of installing a rear PTO and any under-the-bed lift, and ending the Farm Jeep era. Any sales would have been to owners of any of the pre-1970 models, still a significant market. Any guess as to the number of units sold?

EKIII – I don’t know how many units were made. I know back from my memory that it wasn’t a major item for us when we took over in 1967. A few, as I said. I believe I remember a metal plate tag on the backing plate with Stratton information, such as a serial number. I also believe these would come from Stratton for the job. It is a vague memory I have of this.

I also remember my dad looking under my 1977 CJ5 to see what modifications could be made to accommodate a lift. Sadly, he couldn’t make it work.

BT – The three-page parts list is a goldmine for anyone doing a restoration. It is also the gateway to understanding how the lift came together as a finished project. But without your knowledge, it would be like having a list of ingredients and no recipe. Someone might get lucky and guess how everything came together, but we have no need to guess.

Nate Bolduc has sent us some photos of his Stratton lift as it was being restored. They showed the three major components that I believe E&K built. They include the frame, hydraulic cylinder, fluid reservoir tank and the control valve stand.

I realize you were a kid, but can you take us through as much of the lift assembly process as you remember – how parts and sub-assemblies were made, that sort of thing. Of course, we will want to know about your role. What color red paint, where did you place the “Jeep Approved” decals and what got packed in the crate?

EKIII – Downstairs, we had the shear, punch presses, brakes, mechanical hacksaw and welding areas. Upstairs were motor-driven turret lathes (Warner & Swasey WWII-vintage machines with war production tags), belt-assembly-driven lathes with clutch mechanisms (to align the belt with the ceiling drive pulley assemblies), a long bed lathe, milling machines, small planers, drill presses, and a parts assembly area. The freight elevator between the floors was often used as a spray booth. The mechanical spring shear could handle quarter- to 3/8-inch metal, depending on hardness and length.

Most pieces on the backing plate and frame were cut on the Racine Power Hacksaw. Flat-bar stock would be set on roller stanchions, usually three or four lengths of steel high. These would be rolled forward through the vise to a stop or handmade gauge. Length was verified by bringing the blade down unpowered, vise tightened then the saw was engaged. This way multiple pieces could be cut at once. All angle iron was cut this way as well. Plates that were needed could be sheared, if size was small enough, or sawed. The plates would go to a punch press or drill press to have the holes added. Burrs would be removed on a wire wheel. I would operate the saw, and later the drill presses. My brother Dave would move into my place on the saw. These pieces would then go to the welder, who would fit them into a jig and weld in place.

The hydraulic valve mounting plate that was next to the driver’s seat was sheared, the holes pressed in, and formed on the brake. Any shafts or rods were cut on the hacksaw then trued up on the long lathe. Keyway slots would be done on a milling machine.

The hydraulic cylinder was double-acting, requiring two holes and fittings for hoses to the assembly. The cylinder was made completely in-house. We did send the rod out for plating. When the cylinder was assembled, it was taken to a hydraulic test bench to verify operation. It was deadheaded in both directions to look for leaks around the welds. If any were found, they would be marked and the welder would re-weld these areas.

If needed, pieces were buffed with a soft wheel, then cleaned with a solvent. Areas that would not get paint would be masked off. Items were painted Harvester Tractor red, and then assembled. Stratton Decals would be applied to the arms. I also believe there was one on the backing plate. I believe that two “Jeep Approved” decals were used. One on the backing plate and one on the control valve assembly. I’m not absolutely certain about the location, but that is what I remember.

The arms, frame with hydraulic cylinder, and hydraulic hoses would be strapped to the crate. A box with miscellaneous parts would be strapped inside it as well. I believe it contained pins, chain, the control valve, and the hydraulic pump with its mount. Some other items may have come from Stratton to be added. I can’t remember.

We would ship to Stratton, to a dealer, a shop where it was being installed, or to an individual. It would go at Stratton’s direction. Toward the end I know we were shipping replacement parts overseas to Korea and other places that were using wartime equipment in the fields.

BT – I know that a lot of Stratton Lift owners are going to enjoy hearing about how their lifts were made. But before we go, I’d like to ask you about the future. We get requests for sources of lift components (especially arms that seemed to get lost). We also get requests for help finding complete lifts. Would E&K be interested in making replacement parts or maybe even a complete lift?

DK – The short answer is YES. Very much so. We need to run down the rest of the drawings. Items can also be reproduced from measurements of the old parts. I’ve done this many times. We do this for a lot of our other customers, whether UPS or City Utility body parts.

BT – This has been a wonderful experience. Ernie, I want to thank you for taking the time to write me.

EKIII – For me, just looking at the handwriting on the files brought back Dad’s memory. I went into the military because of my dad. He was in the Air Force, and I followed 20 years later. I own Jeeps because of the lift and Dad. I learned that through this experience.

BT – I also want to thank you, Dave, for taking the time to uncover these documents. And I wish the best for E&K.

DK – Thank you. This has been an interesting trip, that has brought back a lot of memories as well. I was a lot younger than my brother, so there has been some catching up I’ve been doing with the lift. We have been referring back and forth on the documents and drawings. I will say there are more to review and will be more to come.

Still more questions

Among the documents uncovered by Dave is a Stratton lift blueprint with the label “Land Rover.” Did Stratton, as Monroe had done, sell the lift for applications other than the Jeep? It appears to be the case and we will do additional research.

Although E&K made most of the lift components, the “power pack” (the hydraulic pump and mounting bracket), were, according to Ernie, obtained from a local supply house. The power pack delivered with the Stratton lift was the same unit used on the late model Newgren (1947) and all Monroe lifts (1948-1956). Finding the manufacturer of the power pack would provide valuable information about all three lifts.

Finally, while Ernie and Dave have not been able to answer several questions about the Stratton lift, they have provided new avenues of research. We plan to revisit those question and hope to rewrite the final chapter of the Farm Jeep story.

About the authors:

Dave Klimek is still involved in the family business started by his grandfather on Cleveland, Ohio’s near westside, where they do welding, fabricating and machining for other manufacturers, as well as utility body-repair work for public utilities and municipalities.

Ernie Klimek III resides in Washington state, retired from Water & Wastewater Utility management. Now an instructor and Apprenticeship and Training Supervisor for Evergreen Rural Water of Washington.

Barry Thomas and his son, Evan, run FarmJeep.com, a Website dedicated to recording the history of Jeeps in agriculture. He can be reached at barry@farmjeep.com

[1] The Making of the Farm Jeep-Part 5, Dispatcher, Fall 2018, page 21

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.