The Making of the Farm Jeep – Part 1

By 1945 Willys was looking to its future and ran ad campaigns highlighting the Jeep’s potential peacetime uses. It’s clear Willys believed that returning GIs would have forged a bond with their jeeps on the fields of war, and the company wanted to leverage that relationship into sales.

Planners for the postwar Universal Jeep, that would become the Civilian Jeep (CJ), believed that they would have a built-in market for industrial applications and agricultural use. The small farmer would be the primary market for the first AgriJeep and its descendants, including the officially named Farm Jeep.

In the late 40’s unpowered (pulled and ground-driven) implements were still the dominant farm tools. Willys played up the fact that a farmer, even if converting from draft animals, wouldn’t need to invest in new equipment. The CJ would be capable of doing farm tractor work, again illustrated by the earliest ads showing the Jeep pulling implements attached to the basic drawbar.

At the same time, the introduction of the Ford-Ferguson hydraulic 3-point hitch in 1939 had begun to drastically change the tractor industry. Willys, as we will see, was well aware that they would be competing directly against this new type of tractor for farmers’ dollars. Almost at the same time the new CJ2a was hitting dealers’ showrooms, a hydraulic implement lift was available.

In this article and those that follow, we and others will look at the four “Jeep Approved” hydraulic lift systems that transformed the post-WWII civilian Jeeps into a useful two-bottom plow tractor. We will begin with the first, the Love Lift, and follow with the Newgren Lift, the Monroe Lift and, finally, the Stratton Lift. While these lifts weren’t the only equipment that made a “farm jeep,” they were a strategic addition.

To understand the history of the Jeep lifts, we need to go back before the Jeep was even on the drawing board. Two men, Charles Sorensen and Jabez Love, who would become key designers of the civilian jeep in its farm configuration, are already deeply involved in tractor building long before they came together at Willys during WWII.

Charles Sorensen was known as Henry Ford’s right hand man. Sorensen was instrumental in Ford automobile, truck, and tractor production from almost the beginning of the company until 1943. In the mid-1900s, Henry Ford took time away from automobile manufacturing to produce a farm tractor (the Fordson) and Charles Sorensen went with him. Later, Sorensen was also involved in the development of Ford-Ferguson system and the 9N tractor. Although best known for his role in the development of the moving assembly line and the Willow Run plant, which produced the WWII B-24 bomber at the rate of one plane an hour, it is his experience with farm tractors that interests us.

In 1944, Sorensen had left Ford to head Willys-Overland. He is credited by many as having led the design of the Willys CJ. Prior to leaving Ford Motor Co, he had been responsible for production of all Ford’s defense contracts, including the Ford version of the Jeep. It is impossible in a paragraph or two to detail why Sorensen is such a key player. But, as you can see, he came to Willys with an in-depth knowledge of farm tractors (specially the Ford 9N) and the military version of the jeep. To truly understand the experiences Sorensen brought to Willys, we would encourage you to read his book listed in the sources at the end of this article.

The other person of special interest is Jabez (J. B.) Love. Love was a young engineer from Michigan who in the mid-1930s saw a need for a new type of farm vehicle. He had observed the fruit farmers of the area gathering their crops from the fields, transporting them to the barn, and then loading them onto trucks for the trip to the market. Love thought it a waste of time and labor to handle the crop twice. What was needed was a way to take the wagons from the fields directly to the market. To solve this problem Love made a tractor out of a model ‘B’ Ford motor, truck transmission, and truck rear-end, and called it a “TRUCTOR.’” The farmer could go from field to market traveling on the roads at about 40 miles an hour. Mr. Love made these “tructors” from 1933-1936.

Love would continue to build his specialty tractors until the mid-1950s, although he dropped the “TRUCTOR” label for the “Love” emblem and a futuristic design in the late 1930s.

In 1939, Love saw a demo of the new Ford 9N tractor with the Ford-Ferguson system hydraulic implement lift. Love immediately purchased a Ford tractor dealership in his home county. While Love continued to manufacture tractors, it is clear that he saw the 3-point hitch as the future of farming.

Love found that farmers didn’t want to buy the new Ford tractor because it lacked a disc, a basic farming implement and a requirement for the local field and orchard work. While Ferguson had developed a line of implements for the then new 3-point lift, he didn’t include a disc. This appears to have been done at the request of Henry Ford. Mr. Ford was concerned that a heavy disk would cause the tractor to flip backwards, a common problem with Ford’s first entry into tractors, the Fordson.

Love quickly fabricated a disc to work with the hitch and based on customer demand, he developed his own line of 3-point implements by the end of 1940. He described himself as being in the implement business, having switched from the more competitive tractor manufacturing. (For more information on Jabez Love’s tractors, see the sources section at the end of this article.)

The next we hear of Mr. Love, he is working as a consultant to Willys-Overland during the war on the design of the post-war Jeep. It isn’t clear how Love come to be involved with Willys. Love’s company was located in Eau Claire, Michigan, so not that far from the automotive center of the universe. Love had a history with Ford Motor dating back to his use of Ford components for his “tructor” and his Ford Tractor dealership. Perhaps J. B. Love had developed a relationship with Charles Sorensen. We know that Willys was looking at a combination truck and tractor design for the civilian Jeep. Could Sorensen have been the one to bring Love in as a consultant based on his “tructor” experience? Or did Sorensen bring Love to Willys to develop an add-on hydraulic lift system that would make the CJ a direct competitor to Ford’s 9N/2N tractors?

Sorensen never wrote about his time at Willys-Overland, but as stated above, we know that he would have extensive knowledge of the Ford tractors and we also know that tests of Ford tractors and Ferguson implements were carried out at his farm. Although, as we have stated, early ads showed the CJ as a pull-type tractor, Sorensen would have known the Jeep would need a hydraulic system to be competitive in the tractor market. We believe, but may never be able to prove, that Sorensen would have been the force behind the lift design that would allow the use of Ferguson type implements.

However, we can’t ignore that Love may have been looking for an outlet for his own implement line. He clearly had the engineering skills to design the lift. Unfortunately, Love, like Sorensen, never wrote about his time at Willys. So the speculation will continue. But it seems unlikely that Love would have had the business expertise or position to form an alliance with Willys to sell a hydraulic lift as was done by the Monroe Auto Equipment Company just two years later.

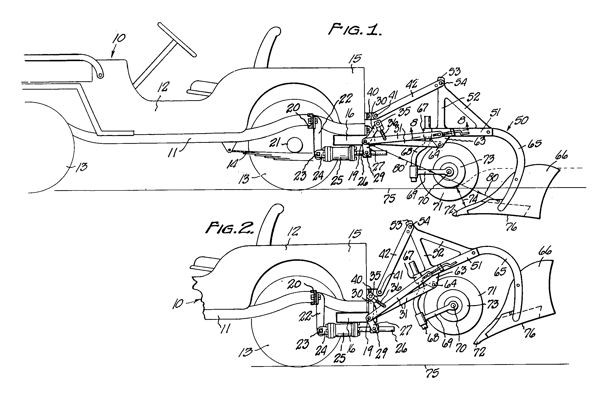

3 Original style Love hitch

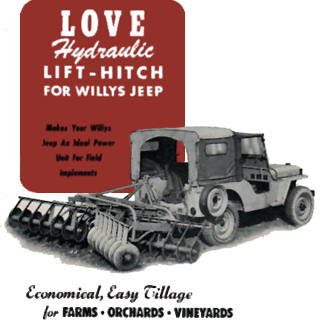

Regardless of how Love’s relationship with Willys came about, we know that by 1946 Love had developed and patented a 3-point hydraulic lift for the new CJ2a. Luckily, over at FarmJeep.com, our friend Jeff Szucs sent us a copy of a combination sales brochure and installation instructions that Love used to promote the new lift. It provides details and pictures that we can use when comparing the Love and the later Newgren design. It is interesting to note that the cover page shows the lift in action, with Love’s 3-point disc.

The importance of Love’s 3-point hitch design in agricultural history has gone unreported. While the war had disrupted tractor and farm implement production, demand was high in the post-war years. Farmers wanted hydraulic lift systems like Ford’s for their tractors. In the 1940s and 1950s the big companies, John Deere, International Harvester, etc. developed their own proprietary systems for lifting implements and required the farmer to buy new implements that worked with the manufactures’ new lifts. Implements were not interchangeable between brands. It wasn’t until the 1960s when the early patents expired that the industry settled on the 3-point hitch standard as developed by Henry Ford and Harry Ferguson.

While in hindsight it would seem to be the logical approach to design a Jeep lift that would use industry standard implements, as noted, those standards didn’t exist in 1945. Yet, here is Jabez Love designing a system that withstood any patent fights with Ford-Ferguson. Love also designed his system in a manner that made the Jeep a true “Universal” vehicle, capable of changing forms in minutes (if not seconds). Pulling 5 pins (2 pins holding the long arms to the short arms, 2 pins holding the long arms to the lift and 1 pin on the top link) to transform the “tractor” back to a pickup ready to hit the road.

From 1946 until the 1960s, any farmer wanting a tractor with a Ferguson compatible 3 point hitch could buy a Ford, a Ferguson, or a Jeep. (There was also an Empire tractor made from Jeep parts and a Love Lift, but few were produced.) Why did Ford and Ferguson allow Love’s patent to be awarded? Perhaps Love had guidance from Mr. Sorensen who would have had intimate knowledge of the Ferguson system. Or perhaps it was because the patent was for the Jeep and not a tractor. There may be undiscovered lawsuits, but we believe they would have been reported. We do know that Love sued Ford Dearborn over the design of the 3-point disc. Love was involved in other suits involving his implements, but never, apparently, over the design of his lift. This may remain one of the most puzzling aspects of the “Farm Jeep” story.

The Love Lift set the design standards for those that follow. There are issues with the Love (and Newgren) Lift regarding the 3-point geometry. While most standard implements work well with the lifts, plows are problematic. You may notice that the plows pictured in ads and articles have a short “mast,” that part of the plow that connects the plow to the 3-point hitch’s third or top link. Love had lowered the top link mounting point by a few inches to allow for normal operation of the CJ’s tailgate. Those few inches altered the plow geometry enough to require the short mast design of the plow. Farmers will tell you that plowing is all about geometry and while Ferguson plows would work with the lift, the modified plow performed much better. Monroe would use these plow performance issues as one reason for the design changes that put the lift in the bed of the Jeep. (There will be more discussion about the Monroe design in future articles.)

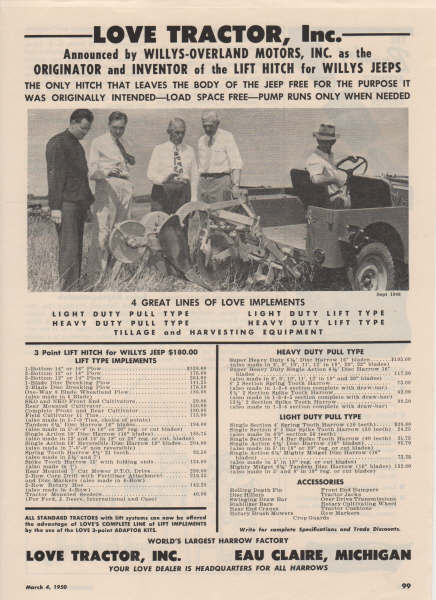

While we don’t know the number of Love lifts produced, we do know that he continued to advertise them for sale as late as 1950. He had increased the price of the kit from $150 to $180. We have neither found references to the lift in any of the antique tractor articles covering Love, nor have any of the owner/collectors of Love tractors been able to provide additional information.

In the headlines of the 1950 ad, Love does take a direct jab at the Monroe Lift design. He correctly states, as we will see, that his system was the original system announced by Willys-Overland and that it “… leaves the body of the Jeep free for the purpose it was originally intended…”

The Love Lift and its transformation into the Newgren Lift will be told in the next installment.

———————————————-

Sources:

Sorensen, Charles E. My Forty Years with Ford, 1956

Westerman, Bob. “Love 3-Point Hitch.” The CJ-3A Information Page. http://www.cj3a.info/acc/2love.html

Hall, Robert Jr. “LOVE Tractor Story.” Gas Engine Magazine. http://www.gasenginemagazine.com/farm-life/love-tractor-story

Zoschke, Paul, “Love Tractor. Inc.” Antique Power Magazine. Sept/Oct 1997